"Free time" doesn't exist

...at least in the wild. In today's world it needs cultivation and care.

One of my favorite quotes about rest comes from John Lubbock, in his essay "The Uses of Life:"

Rest is not idleness, and to lie sometimes on the grass under the trees on a summer's day, listening to the murmur of water, or watching the clouds float across the blue sky, is by no means a waste of time.

Lubbock was one of those Victorian polymaths who cultivated interests in many fields, yet he knew the value of rest. When he wasn’t running his bank, sitting in Parliament, on archaeological digs, or out riding or playing cricket, he entertained on his estate outside London (his next-door neighbor was Charles Darwin), and advocated for rest for others. His most enduring legislative accomplishment, in fact, was the creation of bank holidays.

I was thinking about the image of lying on the grass and listening to the water after a conversation about implementing 4-day weeks, and why companies can't use simply use time savings from automation, shortening meetings, etc. to do more work.

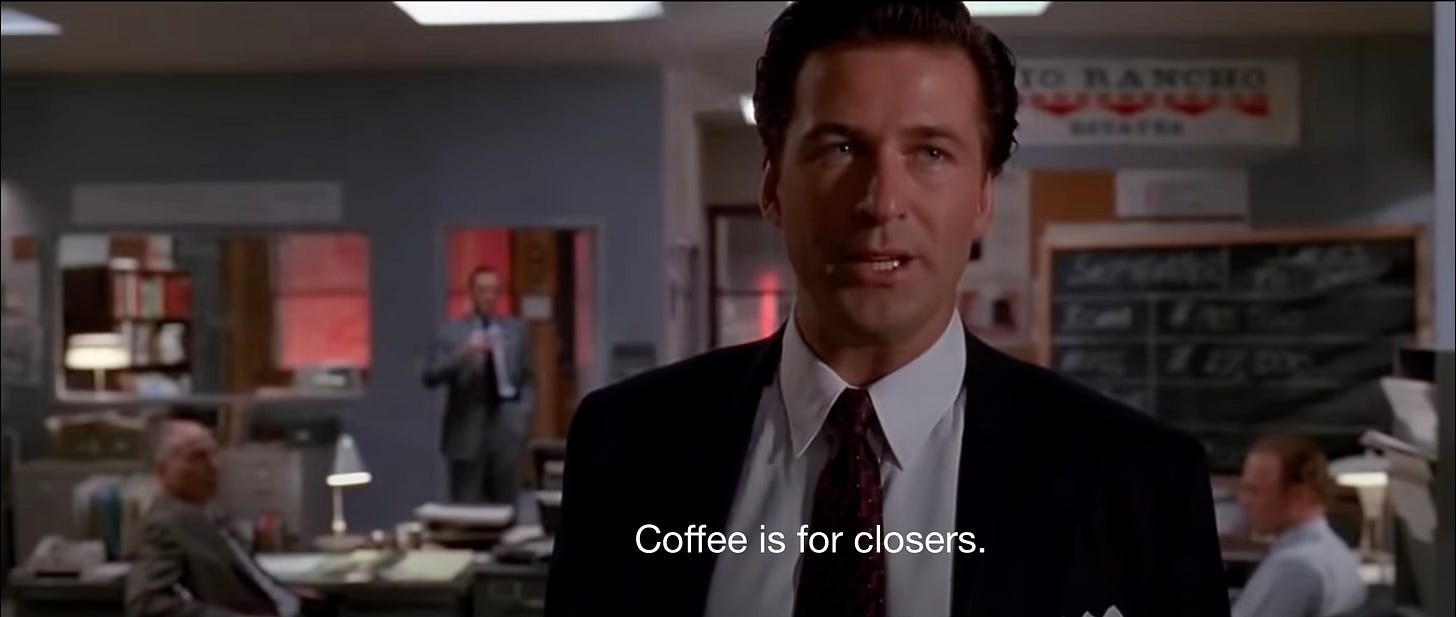

Behind this question is a powerful assumption: that long hours equals success, and longer hours equals more success. Just as important is its corollary: that working less is unilateral disarmament. This attitude is perfectly summarized by the quip by Aadit Palicha, the 22 year-old CEO of an online grocery delivery startup: “I have nothing against work-life balance. In fact, I recommend it to all our competitors.”

You might as well give your sales leads and clients to the competitor who’s staying late.

The implication is that working time can only move in one direction: greater intensity, longer duration.

Nobody planned this; as Brett Scott puts it, it’s the logic of the system:

technology is never used to save time. It’s used to speed up production and consumption in order to expand the system. The basic rule is this: technology doesn't make our lives easier. It makes them faster and more crammed with stuff.

It also reveals a deeper problem in modern life: the disappearance of free time as something that just exists in our smartphone-clutching lives, rather than something we have to create.

All kinds of things promise to create more time in our lives. But because there are a seemingly endless number of other things waiting for our attention at work and at home, as soon as we create space in our calendar, something will rush in to fill it. Less time in meetings means more time for clients; time-saving automations mean more sales calls; time saved at home becomes time to drive the children to another activity. And when there aren't external demands on our time, there are internally-generated ones: FOMO, perfectionism, the sense that you need to keep busy, are all harsh taskmasters.

This is a problem because, as Seneca put it a couple millennia ago, “busy men find life very short.”

The condition of all who are engrossed is wretched, but most wretched is the condition of those who labour at engrossments that are not even their own…. If these wish to know how short their life is, let them reflect how small a part of it is their own.

As a consequence, for most of us, free time can no longer exist without conscious cultivation. Like a dystopian science fiction movie where clean air or grass only exists in geodesic domes, free time is no longer found in nature.

In today’s always-on world, you don’t just save labor and then sit back and enjoy the benefits. (Indeed, labor-saving technology rarely saves labor in the way we’re told it will, as Ruth Schwartz Cowan’s classic More Work for Mother explains.) Creating free time has become a two-step process: you find a way to make a task that takes X minutes take Y minutes, and then you need to protect those new X-Y minute savings from your boss, the Little League snack signup sheet, your spouse, and Instagram. You’ll only succeed if you have a plan for what to do with that time, and ways to ringfence it from all the demands and distractions that want to claim it.

This is not to despair at how terrible modern life is (for all its challenges and distractions, I’ll take the longer lifespans and insanely easy access to information); but it is to say that you have to be more strategic and ruthless about how preserving your free time, or work with others to create and protect free time together.

Recent interesting 4-day week links

Jean-Yves Boulin has conducted a pretty thorough review of the 4-day week literature, and the preprint version is available here.

The municipal government in Tokyo is talking about allowing government workers to shift to a (longer) 4-day week in an effort to boost birthrates. Discussions about the 4-day week in Japan and Korea are often connected with worries about reproduction rates.

In Australia, in the wake of insurance company Medibank and accountancy Grant Thornton trialing shorter weeks, the Financial Sector Union is pushing for a 4-day week in other companies, and negotiated a shorter week at Insignia Financial.

Dr Charlotte Rae, PhD and Emma Russell "argue that improved performance on a 4-day working week arises through two psychological mechanisms of recovery and motivation: because better rested, better motivated brains, create better work."

4 B Corps Share How They Make a Four-Day Workweek Work

One remarkable song

I’ve been listening to a lot of music lately, and reading about the music industry, because I have think a lot of the debates we’re having about automation, workplaces, and the future of work involve things that the music industry has been dealing with for decades. Mobile work? The Rolling Stones created the first mobile studio, which they used to record Sticky Fingers and Exiles on Main Street (and is mentioned in Deep Purple’s “Smoke on the Water”— you know, “We all came out to Montreux / On the Lake Geneva shoreline / To make records with a mobile, yeah / We didn't have much time”). Home office? Home studios have been a serious thing since the 1970s, when Pete Townshend ran a company that built home studios for musicians, and Steve Winwood recorded his comeback Arc of a Diver at his home studio in in Turkdean, Gloucestershire in 1978-79. And don’t even get me started on gig work, precocity, conventional publishers destroyed on online incumbents, etc.. And on the upside, there’s a lot we can learn about collaboration, long-lived partnerships, creative careers, etc.

One of the unexpected pleasures of doing this work is that I will sometimes come across an artist I’ve never heard of, or be inspired to catch up with a band I listened to in my youth but lost track of. I have enough of these to start sharing them now and then. So:

Rising Appalachia, “I Shall Be Released.” [Apple Music and Spotify] Centered around sisters Leah Song and Chloe Smith, Rising Appalachia has roots in folk but branches out in all kinds of interesting directions. Their version of “I Shall Be Released” is fabulous, a simple arrangement that shows off their voices and highlights to poignancy of the song.

Here’s a live version:

It seems like this post is trying to highlight Jevons Paradox without saying it explicitly . https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jevons_paradox can you confirm that?

When it comes to the implications of this paradox in this new age of generative AI, this following paper highlights the pessimistic pathway described in the book "more work for mother" that you highlighted.

The Ethical Implications of Artificial Intelligence (AI) For Meaningful Work

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10551-023-05339-7

Overall, we show that AI has the potential to make work more meaningful for some workers by undertaking less meaningful tasks for them and amplifying their capabilities, but that it can also make work less meaningful for others by creating new boring tasks, restricting worker autonomy, and unfairly distributing the benefits of AI away from less-skilled workers. This suggests that AI’s future impacts on meaningful work will be both significant and mixed.