Technology and Creative Collaboration

What Jimi Hendrix and Proctor & Gamble can teach us about innovation, new ideas, and creative partnerships

“The thing with Jimi is that each tone was crafted almost all at the time right in the studio, to correspond to the portion of the song that he was recording,” Roger Mayer is telling me. I had emailed Mayer to ask him a couple questions about his work, and unexpectedly he phoned me back a few hours later, and was explaining how he and Jimi worked together. In the late 1960s, Mayer had developed the pedals that Hendrix used to incredible effect on his albums Are You Experienced, Axis: Bold as Love, and Electric Ladyland. The distortion and echo on "Purple Haze," "Voodoo Chile," and other classics? Jimi created those with Mayer's pedals. I've literally spent my whole life listening to work that Mayer helped create, and only recently have I come to appreciate how close their collaboration was.

More than fifty years on, it’s hard to appreciate how novel Hendrix’s sound was. He was recognized by his peers as one of the most talented guitarists of his age— an age that included Jimmy Page, Jeff Beck, Eric Clapton, Pete Townshend, and many other greats— but his creativity went beyond that. Previous guitarists had treated electronics and effects pedals as a novelty, but Hendrix realized that they could vastly expand the expressive power of the guitar. He didn't just use those pedals in his production; he made them creative tools as well. But in the late 1960s, you didn't plug in an off-the-shelf effects pedal; commercially-available pedals had limited capabilities and highly variable quality. Innovation required inventing those pedals, then exploring what they could do. Roger Mayer built the pedals that Hendrix used, while Hendrix showed Mayer how they could be improved to further expand the bounds of musical expression.

Hendrix's collaboration with Mayer is among the most important in the history of music, but it's not just aging music lovers who can appreciate it. If you look past the glare of drugs, bad behavior, and bacchanalia, it turns out that the history of popular music offers an immense amount of raw material about successful creative collaborations. This has always been important for creators, knowledge workers, and enterprises that depend on new ideas; today, the growing use of generative artificial intelligence makes it even more urgent that understand how to design processes and technologies that help us be more innovative.

AI and Innovation

People have been studying human-machine collaboration for decades, and recently researchers have turned their attention to how teams use AI, and how using AI affects team performance, cohesion, attitudes towards work, etc. A subset of this literature focuses on the impact of AI on innovation. Innovation often involves drawing on ideas, materials, or practices from different domains, and combining them in unfamiliar and unexpected ways. These days, that often means applying new technology in fields that hadn't been very technical.

We're most familiar with technical innovations applied to products (think of smart appliances that can be controlled via the Internet, or athletic clothing made from technical fabrics), and to a lesser degree with innovations in manufacturing (interchangeable parts, mass-production lines, photolithography, 3D printing); but it's also possible to apply new technology to the creative process itself.

A Novel Experiment at Proctor & Gamble

Bringing together groups with different kinds of expertise is one of the classic ways R&D labs and companies seem to make more creative teams. One place that does that most consistently is Proctor & Gamble, the consumer goods giant. You might not imagine that a place that makes paper towels, diapers, toothpaste, and snacks is interested in innovation, but they’ve thought a lot about how to create products, and turned that into a set of practices that they use regularly. (Yes, creativity doesn’t mean exactly the same thing when you’re dealing with billion-dollar brands like Tide and Bounty as it does when you’re got an empty reel of tape in a studio, but if maintenance is serious work that doesn't get the love it deserves, maybe innovation in large enterprises can also get a little respect.)

As Fabrizio Dell'Acqua and a team of researchers realized, this makes P&G a great environment in which to conduct an experiment on the impact of AI in one part of the creative process: the generation of new ideas. As their article explains, "P&G emphasizes this early 'seed' stage as a crucial element in their entire innovation process. A senior leader at the company emphasized that 'better seeds lead to better trees,' reflecting the importance of high-quality ideation."

Here’s what they did. They assembled teams to come up with new product ideas. People were assigned to one of four kinds of teams: one-person teams; two-person teams with people from R&D and Commercial; solo worker + ChatGPT; and two-person teams + ChatGPT. The AI teams were given an hour’s training on the technology, and some prompts they could use. Here are a couple of the prompts:

You are an incredibly smart and experienced research assistant asked to gather information to help analyze the following problem: [Insert Problem Statement]

First introduce yourself to the team and let them know that you want to help the team begin their research process.

Second ask them for any documents they might have to help you with research.

Then ask the team a series of questions 2-3 about the problem (ask them 1 at a time and wait for a response).

The results of the ideation sessions were reviewed by senior executives. For participants, this was a familiar kind of work, of a value that everyone recognizes, done using a process that they all know. So what happened?

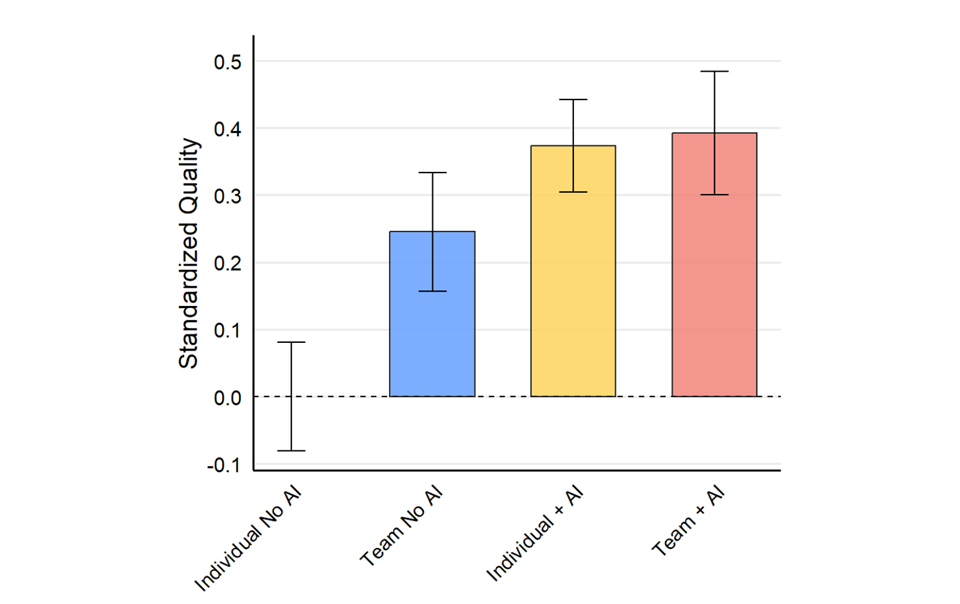

First, if you look at the quality of the ideas they generated, teams consisting of a human + AI outperformed two-person teams. Two-person teams + AI did slightly better than the one-person + AI teams.

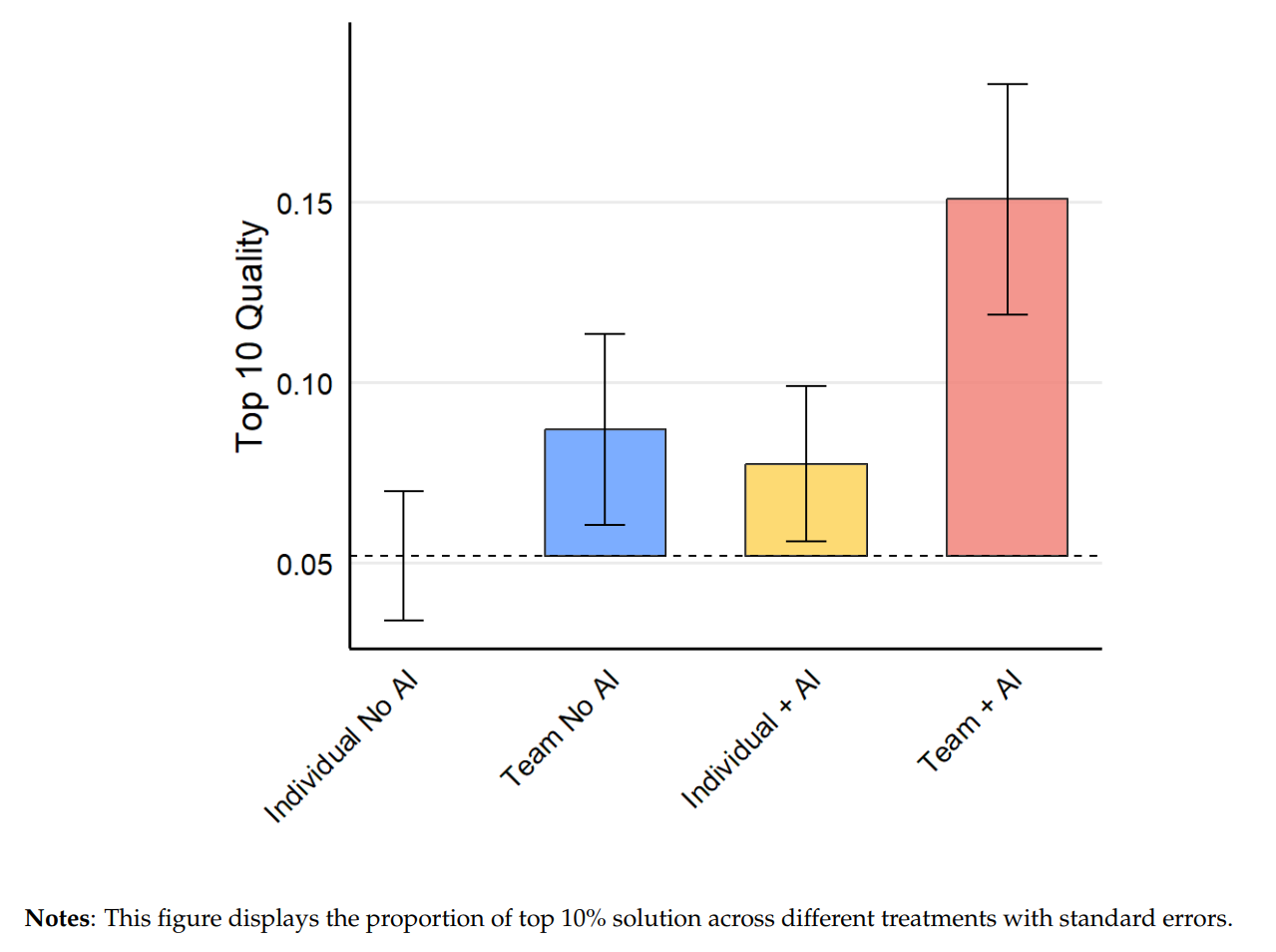

What's even more interesting is who produced solutions that were considered top-tier. The 2-person + AI teams did waybetter than everyone else, including the individuals working with AI:

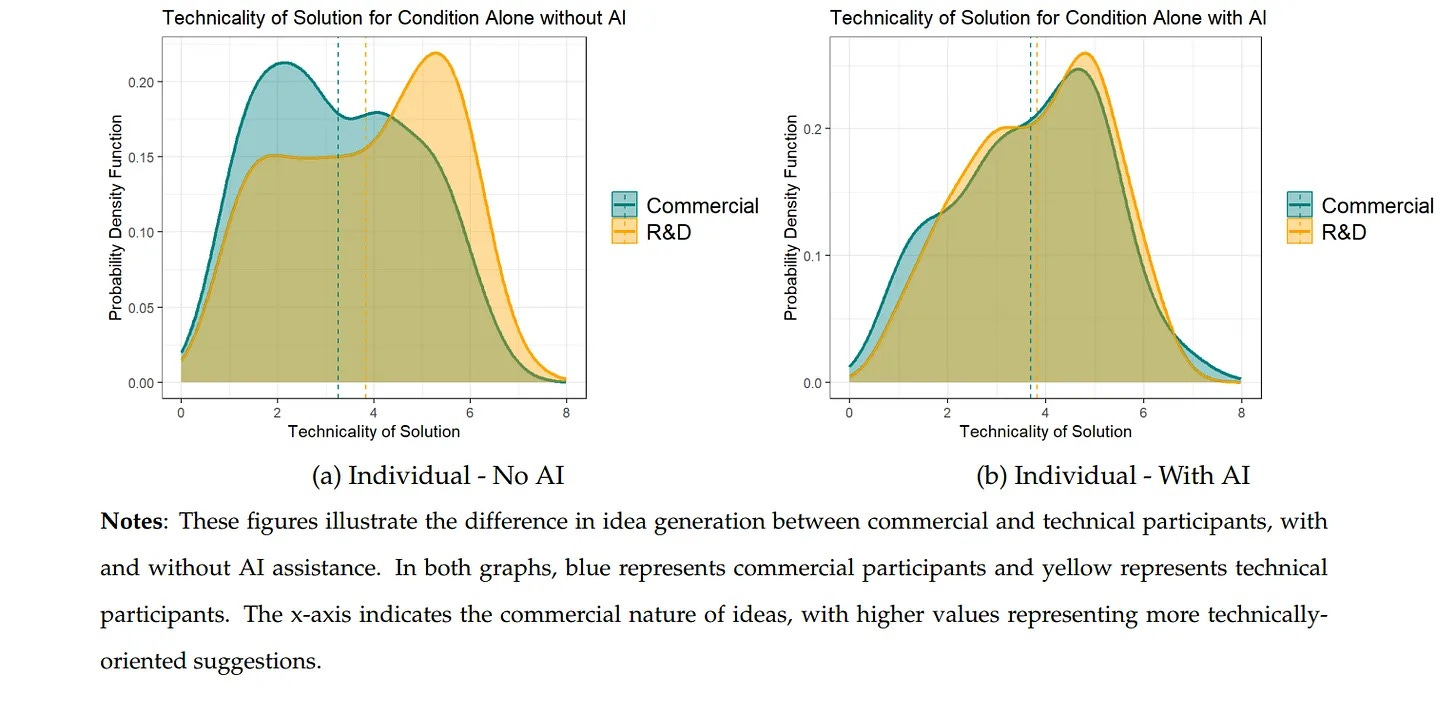

Working with AI also helped break down siloed thinking. Team members had either R&D or marketing backgrounds, but both teams and individuals ”using AI produced balanced solutions, regardless of their professional background.” What the graph below shows is how individuals working with AI came up with more integrated solutions.

You can see how this is an exciting development if novel solutions or creative insights involve reaching across disciplinary boundaries or finding connections between different ideas. Groups who are able to work with both technical and commercial ideas (in P&G's case) are in a better position to come up with really novel ideas.

The Hendrix-Mayer Collaboration

The collaboration between Jimi Hendrix and Roger Mayer likewise combined skills from different realms, united by a shared creative vision. Hendrix was a journeyman blues guitarist who had spent years as a studio musician and guitarist for the Isley Brothers before relocating to London. Mayer came "from a family which has always owned engineering factories," he recalled in 2011; "I grew up around machines and watching my Dad create tooling and prototypes." He worked for the Royal Navy, focusing on "vibration and acoustic capture and analysis, so in reality, it was closely connected to creating guitar tones."

For all their differences, though each was brimming with ideas about how to expand the sound of the guitar, and transform the simple fuzz and overdrive that had been used by earlier guitarists into something more expressive. Hendrix had been pushing the boundaries of guitar playing for years, and had taken sonic inspiration from all kinds of unexpected sources. When he was in the Army, he "told his army pals that he wanted to capture 'air sounds' on his guitar like the ones he heard in jump school training: the droning roar and rumble of the plane's engines, the rush of wind cascading past the ears on the journey back to solid ground." Guitarists were experimenting with fuzz effects, but because of large variations in manufacturing and circuit quality, pedals delivered inconsistent results. Until they had better quality control and more knowledgeable design, they would remain as useful as a guitar that wouldn’t stay in tune.

Mayer had noticed. As he told Led Zeppelin author Bob Spitz, Mayer had listened to his friend Jimmy Page's fuzz pedal, declared that it "sounded mechanical and, quite honestly, boring," and offered to rebuild the electronics. The experience opened up something in Meyer: here was a way to transform the sound of the guitar, and use electronics in ways no one had imaged.

Mayer met Jimi Hendrix backstage before a concert in January 1967. He showed Hendrix the Octavia, a pedal that doubled the sound of his guitar by reproducing a note, then transposing it an octave higher. Hendrix, Mayer recalled, "was so impressed and excited with the new sounds he invited me along to the Olympic Studio later that week to overdub the solos on his second release—'Purple Haze'—and 'Fire.'"

That launched a whirlwind of innovation in 1967. "Jimi wanted to sound nothing like anything that been recorded before—we wanted to look ahead, not over our shoulders," Mayer said. They worked in Jimi’s apartment, in the studio, and on the road (though eager fans stole several of Hendrix’s pedals). “If we were hanging out up in the flat, you know, like talking, there would be a guitar there, and an amp there, and this and that,” Meyer tells me. “And I’d bring a few boxes up there, and we’d play around with those, and we’d get an idea of the windows that we were operating in.” Understanding those “windows” was important for Jimi because it gave him a sense of the sounds he and his guitar could create with Roger’s latest pedals. On Mayer’s side, watching Jimi experiment with the latest box, or listening to “the song that he was writing at the time” gave him a feel for what Jimi was trying to communicate or the feeling he wanted to express, and helped Mayer figure out “what I could do electronically to enhance it or help it,” he says.

As Mayer tells it, Jimi’s understanding of the “window” that Roger’s latest pedals afforded him was akin to an athlete’s understanding of a field and ball: you want to know them intimately not because you can plan what you do, but because it lets you improvise more skillfully. “We knew the window of how the sound should sound,” he tells me, but “it would be impossible to have a really fixed preconception of exactly how it’s going to sound” when Jimi played in the studio or before an audience. Whether in their apartment, the studio, or on stage, the whole point was to create sounds no one, not even the two of them, had ever heard before. You can’t plan that moment. You can only plan for it.

That collaboration and exploration continued in the studio, and Jimi needed Roger in the studio from “Purple Haze” forward. “Each tone was crafted almost all at the time right in the studio, to correspond to the correct portion of the song that he was recording,” Mayer tells me. Sometimes Mayer would change the pedals during recording sessions. "If something had to be changed, I could go into the back room of the Olympic and change the capacitor and tune it up for that track,” he recalled in 2018. Hendrix’s manager Chas Chandler was well-known for not wasting time in the studio, so at Olympic this was more like tuning than engineering, though “the maintenance room gave me access to soldering equipment, so I could I could change a few components if I needed to.” Of course, they took the studio time seriously: recordings were important commercially. But every record was a snapshot, a specific performance: Jimi aimed to never play a song the same way twice.

Lessons

So how does all this relate to P&G and collaborating with generative AI?

First, both stories challenge the stereotype of creativity as a solitary enterprise, and highlight the fundamentally social nature of innovation.

Everyone knows Hendrix, but very few people know about Roger Mayer. Mayer never claims credit for Hendrix's playing; he sees himself as supporting Hendrix, as creating new possibilities that only Jimi could exploit. Recall that Mayer had already done some work for Jimmy Page and Jeff Beck, yet he saw enough potential in Hendrix to focus on their collaboration. But there's no question that his pedals and collaboration helped Hendrix push his music in new directions.

At P&G, their innovation process is designed around the idea that multidisciplinary teams can, under the right conditions, come up with more innovative ideas than siloed groups. In the AI experiment, teams with people from both the R&D and Commercial sides outperform siloed groups; and one important role AI plays is helping them think outside their disciplinary boxes.

The fact that it's very easy to anthropomorphize the experience of using generative AI systems like ChatGPT, and to feel like you're working with a person in a way you never do when you're using a spreadsheet or PDF, helps with this process. I've trained a couple AIs, and working with them feels rather like I'm interacting with a person, despite often having to explain what I want them to do in greater detail than I would a person. (But I even anthropomorphize that: to me these AIs are like interns who are keen to be useful, but need the work explained to them.) It's notable that the prompts researchers gave their subjects cast the AI in the role of "an incredibly smart and experienced research assistant;" the prompts prime both the AI to mimic this kind of behavior and the human to think of the AI as a coworker. Rather than see this anthropomorphism as a bad thing, in this context, it looks a bit more like a benefit.

Second, these stories tell us to design creative sessions in ways that give everyone the opportunity to serve as a collaborator, not just an assistant.

Jimi Hendrix didn't just buy Mayer's pedals, or treat him like a guitar tech who could maintain his instruments; he brought Mayer into the studio, and leaned on him for help to realize sounds that were only in his head. The history of popular music is full of invisible technicians like Mayer, who are overshadowed by both the artist and the work itself, but who make essential contributions to an artist's sound and career. (The term "invisible technicians" was coined by historian of science Steven Shapin to describe laboratory assistants who are airbrushed out of history, but who play an essential role in scientific experimentation and discovery. Lots of professions have invisible technicians.) Likewise, while it's easy to think of AI as either a challenger or a solution machine, the P&G experiment shows that when people treated the AI more as a partner, it helps improve the quality of their ideas.

Third, they advise us to give people control over how new (and potentially threatening) technologies are used.

One of the smart things about the P&G experiment is that the humans on the teams were in charge throughout: they gave ChatGPT the prompts, and built on the responses. The humans weren't being deskilled; rather, the group's capacity for coming up with innovative ideas was augmented. Other studies of AI and creativity have found that AI can be helpful as an idea generation tool, but isn't as good at coming up with original ideas; but people who struggle with brainstorming can use ChatGPT to jump-start creative ideation. In a study that Dell'Acqua and colleagues conducted at Boston Consulting Group on AI use on different kinds of tasks, they found that some consultants worked as "Centaurs," "dividing and delegating their solution-creation activities to the AI or to themselves," while others "acted more like 'Cyborgs,' completely integrating their task flow with the AI and continually interacting with the technology." As they note, AI is pretty good at some things, but dreadful at others, and knowing when AI is reliable, and how to use it to improve the outcome of a complex task, requires judgment-- and that in turn means giving workers control.

Finally, they show that processes that allow for rapid iteration can be really powerful.

One of the features of generative AI is that it's fast: ask it for ten ideas for a catch-phrase for a new kind of sunscreen, and it'll come back to you in seconds. Eight of them may be terrible, but one or two could be interesting enough to build on. In both the P&G and Boston Consulting Group studies, subjects were able to generate more ideas working with AI than working alone.

The collaboration between Hendrix and Mayer was an almost textbook example of what we now call rapid prototyping, a rapid cycle of building, testing, learning, and rebuilding. Mayer built the Octavia that Hendrix used when recording in "Purple Haze" in February 1967. They then threw it away, because Mayer thought he could build a better version. They learned from each song, and Meyer was redesigning pedals as quickly as Hendrix could record new songs, then making new versions, drawing on his father's electronic business for parts or custom-made cases. One model followed another-- fifteen generations of pedals that year alone, Meyer estimates, varying the electronics, casing, and ergonomics as Jimi's playing evolved.